Advent in the Crusader Kingdom

During the Middle Ages, Advent was far more than a countdown to Christmas. In the crusader city of Acre, it became a season of discipline, prayer, and readiness, especially for the English Hospitallers of St Thomas of Canterbury. Founded in 1191 by crusaders serving under Richard the Lionheart, this small but influential order wove together English religious custom, Holy Land necessity, and the broader Latin hospitaller tradition.

Their approach to Advent offers a vivid glimpse into how medieval religious knights balanced penitential fasting, charitable service, and military responsibility in a turbulent world.

A Crusader Order With English Roots

The Order of St Thomas began as a simple infirmary to treat English pilgrims and wounded crusaders. Within decades, papal confirmations from Popes Celestine III, Honorius III, and Gregory IX defined the order’s dual mission:

- cura peregrinorum — caring for the sick and pilgrims

- defensio Terrae Sanctae — defending the Holy Land

This combination of charity and knighthood shaped the brothers’ spiritual life, especially during seasons such as Nativity Lent.

Advent as a Penitential Season

Across the medieval Church, Advent was treated as a “little Lent.” Clergy and religious observed reduced meals and abstinence from meat. Both Latin East customs and English ecclesiastical statutes reinforced these expectations.English founders of the Order brought with them canons from Canterbury and London that clearly required:“Jejunium Adventus Domini cum abstinentia a carnibus…”

“The fast of the Advent of the Lord with abstinence from meat…”Thus, Advent fasting became a defining spiritual duty for the brothers of St Thomas.

How the Order Observed Advent Fasting

Despite the fragmentary survival of their rule, historical reconstructions reveal several key Advent practices among the brothers.

1. Abstinence From Meat

The rule stated plainly:“In Adventu Domini carnium abstineant fratres…”

“In Advent the brethren shall abstain from meat…”Exceptions were granted only for illness or the hardships of military travel. Patrols protecting the roads between Acre, Haifa, and Montmusard often required such dispensations.

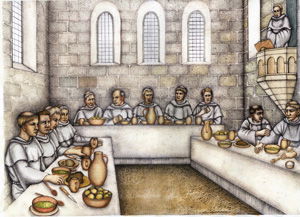

2. Reduced Meals

Following monastic custom, the brothers ate:

- One main meal on fast days

- A light collatio after sunset

Fish from Acre’s harbor, vegetables, and coarse bread formed the usual Advent diet.

3. The Hospital Exception

Because tending the sick required strength and constant night work, the master of the hospital could temporarily relax fasting rules for infirmary staff. After Nativity Lent, they often performed additional penance to compensate.

Eyewitness Accounts of Advent in Acre

Although the order lacked an official chronicle, visiting pilgrims and royal clerks recorded their impressions.

Thietmar of Magdeburg wrote around 1210 that the brothers ate “fish and herbs… as if it were Lent,” highlighting the rigor of their Advent discipline.

A clerk in Henry III’s entourage observed in 1251 that their refectory was silent, their drink thinned, and their service among the sick doubled.These accounts show that Advent reflected their identity - a blend of English sobriety, crusader purpose, and charitable devotion.

Balancing Fasting With the Realities of Crusader Life

Popes recognized that military orders in the Holy Land faced unique challenges. In 1254, Pope Innocent IV allowed crusader hospitallers to eat meat during Advent if travel or defense required it - except on Fridays.

This balance ensured that spiritual discipline never endangered the brothers’ ability to protect pilgrims or defend Acre’s walls.

Nativity Lent as a Season of Readiness

For the Hospitallers of St Thomas, Nativity Lent was not simply preparation for Christmas — it was preparation for service. Fasting sharpened their spiritual senses just as their swords were sharpened in the armoury below their hospital.

In Acre’s bustling quarters, beneath the red-and-white banner of St Thomas, the brothers lived out an Advent defined by:

- abstinence,

- silence,

- charitable labour, and

- vigilance on the city walls.

Their Advent discipline bound together the defense of pilgrims, care for the sick, and devotion to Christ in a uniquely English crusader ethos.